The Better of Only Bad Options

The Fed’s back is firmly against the wall and no amount of sanguine Fed-speak or modern monetary engineering is going to do anything to change that fact. Now is the time for action and an honest recognition of what is truly at stake for the economy.

The only reasonable path forward, at this point, is for the Fed to face the challenge head-on and fight inflation with every “tight money” tool at its disposal.

After 13+ years of recklessly “easy money” policy and more than double that duration of literally nurturing “moral hazard” through market bailouts and backstopping (Crash of 87, LTCM, DotCom/911, Housing Bust, COVID) the Fed and the Federal Government have reached the final leg of the “Great Moderation” period and the start of a new era that will be marked by extremes, volatility and a decidedly less temperate tone.

We have come a long way since the waning days of our last most extreme secular cycle when, in 1983, then Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker finally succeeded (determined in hindsight of course, since this fact was still unknown to his real-time vantage point) in breaking the back of persistent inflation by disabusing all market participants of the notion that an easy money environment would soon return.

An article published in the UK’s Sunday Telegraph dated July 10 1983 captured the sentiment well: “Back in 1979 Volcker jerked the Fed Board out of the old habit of playing the monetary game by Wall Street rules. The big shift was the policy change on the money supply. No longer would the Fed jump every time the Wall Street money markets moved a shade over desired limits. The Fed’s old tools of measuring the money supply – the M1, M2 – were refurbished for greater statistical accuracy. The Fed policy was to set a desirable growth rate for the various aggregates and let market rates seek their own level.”

When asked at a congressional hearing in mid-1983 if he thought long term interest rates would ever return to the 5% or 6% range (rates being nearly double that at the time of the hearing) Volcker stated “I hope those days aren’t gone forever. If you have confidence in a stable financial environment over a long period of time, those types of interest rates would be quite normal. It’s going to be very hard to get back to that climate, because everybody has lived through the late 1960’s and late 1970’s.”

Fast forward to today and the legacy of The Maestro, Helicopter Ben and Dovish Yellen and Powell have taken their toll and instilled quite the polar opposite sense in today’s market participants. Speculators, traders, bankers, financiers, business owners and average Americans alike are all dazed by frothy liquidity and simply cannot believe that the easy money regime is actually over.

Watching the business media pundits cycle go through endless loops of conjecture over the prospect of the Fed’s next 25 or 50 basis-point rate hike and whether the peak of inflation may already have been reached given the Fed’s recent action seems laughable in contrast to the severe struggles against “public enemy number one” that persisted throughout the 1970s and 80s when the Federal government even went so far as to engage the public in a misguided and nonsensical battle to “whip inflation now”.

If the fact that 25 or 50 basis points would seem like a rounding error in the era of Volcker were not bad enough, consider that this is happening against the backdrop of a Fed that has made this regime changing lift-off from the literal zero bound.

The market and all its participants are rate-sensitive in the extreme with expectations that are wildly outlandish and even childish as an ever coddled financial system has gotten weaker and less capable of accepting even economic conditions that would have seemed exceedingly favorable for most of modern history.

Further, there is almost a sort of incredulity to this era where many observers express total disbelief that the Fed would (or could) ever actually wage a legitimate war against inflation instead, as some observers predict, choosing to somehow inflate its way out of this inflation problem in an effort to spare the Federal government from the consequences of its own, self-imposed, albeit immense, debt liabilities.

“The Fed does not want to engage inflation, but would rather inflate the debt away…” one observer noted, “always has and always will be the easiest and preferred choice of central banks.” While another observer notes “Hyperinflation or default - both end badly of course. But hyperinflation probably takes longer to play out and is harder to pin blame on than an outright default so it is the preferred option of politicians and central bankers.”

Many even astute macroeconomic observers believe that the Fed will give up on pivoting to a tight money regime and revert back to a loose money posture at the first sign of stress, but is this truly a realistic scenario? Could the Fed be so weak an institution that it will fold immediately shirking its primary responsibility and dooming the whole American economy and particularly millions of American households to a “death by a thousand cuts” future risking general social stability and even the real prospect of a hyper-inflationary end-state?

Let’s look to a short passage from Miami Herald dated October 14, 1979 to gain some valuable real world perspective about the cost of unmoored inflation particularly in the American context:

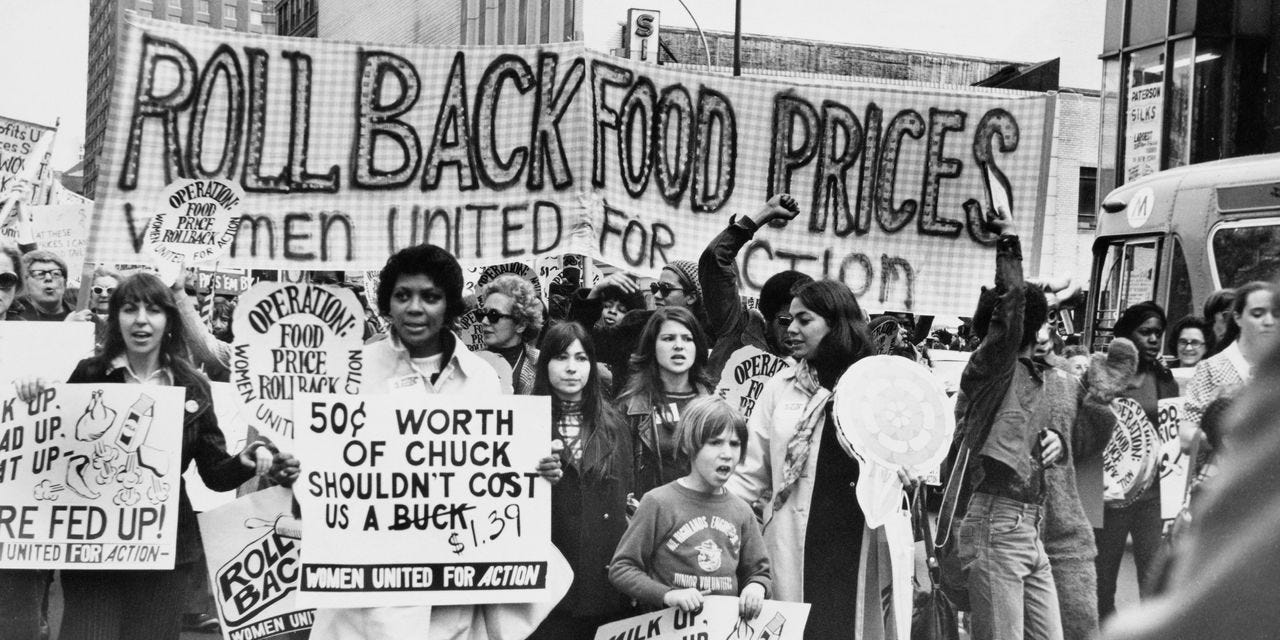

American’s back in the late 1970s learned that letting persistent inflation run amok risked the stability of the entire economic system as every single household, firm and institution struggled to each independently cope with the chaos caused by such extreme economic circumstances. This widespread volatility and ultimately the economic hardship that was caused, was felt unevenly resulting in a sense of inequity that spilled over into the social and political realms creating instability in the truest sense of the term.

The Fed, motivated by the fear of widespread systemic instability, won’t let this happen again.

In 2008, as the economic crisis caused by the collapse of the national housing markets was bearing down on the economy and causing similar hardships to households, firms and institutions (except from an decidedly deflationary perspective), the Fed panicked leading it not only to act but to overreact to the circumstances and stopped at nothing to blunt the effects of that period and, in their view then, rescue the economic system from disaster.

Today will be no different as the Fed recognizes the inflation to be unmoored and persistent and holds firm to the tight money posture in an effort to secure the stability of the overall economic system even as the pain endured by higher interest rates is widely felt.

Granted, this pain will likely most notably be felt by the Federal government itself as the portion of the federal budget allocated to servicing the outsized national debt grows substantially leading to hard decisions about national priorities.

But it is important to note that the entirety of the federal debt doesn’t just immediately get refinanced at higher rates in-line with the Fed’s interest rate policy but instead guides up over time as portions of the existing debt mature and new debt is issued at the prevailing higher rates.

The Federal government will need to make some hard choices in the form of real cuts to spending that will have real measurable effects on some households and firms but as bad as a new era of fiscal austerity may seem, it is unequivocally the better option if given an alternative of the rapidly and even violently eroding living standards and life savings of most Americans coming as the result of unchallenged and unchecked inflation.