Reflecting on Rates

The Fed is way behind the curve on the battle against surging inflation; either they want to fight or they don't, but tepid rate action is not a reasonable approach.

For the last few months now, I have been suggesting that the Fed needs to move the Fed Funds rate up much faster than they have been, arguing that they are not only “behind the curve” given their failed “transitory” position, but that they have totally lost the narrative as far as taking a “hawkish” stance is concerned.

My suggested approach to rate hikes has been for the Fed to move in the range of +100 to +125 basis points at each scheduled meeting (of 2022) as well as implementing random “emergency” intra-meeting rate hikes and setting an overall target of at least 8.5% by as soon as conceivably possible.

Obviously, this may seem a bit extreme from the standpoint of the “recency bias” of our current distorted economic times as well as the current level of debt carried widely by households, firms and the Federal government, but historically, this approach is actually very modest.

The following chart displays the annual rate of change of the consumer price index (i.e. the inflation rate) (in blue), the 30-year fixed mortgage rate (in red) and the effective Federal Funds rate (green) as well as the upper-range target of the Fed funds rate (in light green) in order to present the Fed’s actual current target.

Traditionally, the Federal Funds rate (the green line on the chart above… click for larger interactive version) , particularly during periods where inflation was clearly “unmoored”, has always matched or been well above the rate of inflation as measured by the year-over-year change in the consumer price index (the blue line on the chart above… NOTE: you could also use the annual change of the PCE index, the Fed’s preferred inflation measure but CPI is historically the measure that is reported for inflation as well as the measure feeding into COLA calculations and the like, so I’ll stick with this comparison for now).

Of course, there are notable exceptions, for example, during the two post-recessionary periods following both the “DotCom Recession” and the “Great Recession”, the Fed’s policy rate remained below the rate of inflation for extended periods in an attempt to breathe life back into the respective lackluster economic expansions.

But when it comes to periods where the immediate concern is NOT “deflation” but instead “inflation”, the Fed has either targeted or allowed the Fed Funds rate to float well above the rate of inflation in an effort to contract the money supply and thereby stamp out inflationary pressures.

Shifting our focus to the long-end of the yield curve, another important inflationary relationship is found in comparing the 30-year fixed mortgage rate (the red line on the chart above) to both the consumer price index (rate of annual change) and the Fed Funds rate.

Notice that since the mid-1970s, the 30-year fixed mortgage rate has ALWAYS been well-above the rate of inflation (as well as the Fed Funds rate), which is to be expected, when considering the lengthy maturity of these bonds and the fact that lenders are primarily concerned with the risk associated to the high probability of inflation when pricing this type of debt.

I say “always” but actually since March 2022, the inflation rate (i.e. annual CPI again) has been running above the 30-year fixed mortgage rate and WELL above the Fed Funds rate, a truly anomalous situation that is begging for a resolution.

Either the 30-year fixed mortgage rate has to go up considerably (minimally about 300-400 basis points to 8-9%) or the rate of inflation needs to come down considerably or a bit of both.

One thing is for certain though; the current 1.50% Fed Funds rate is way to low to make a notable difference in either bringing down the rate of inflation or influencing the yield curve enough to instigate the 30-year fixed mortgage rate to guide up.

Remember, I’m certainly not suggesting that raising rates this aggressively is convenient for either debtors (particularly massive ones like the Federal government) or the central bankers at the Fed and their global counterparts.

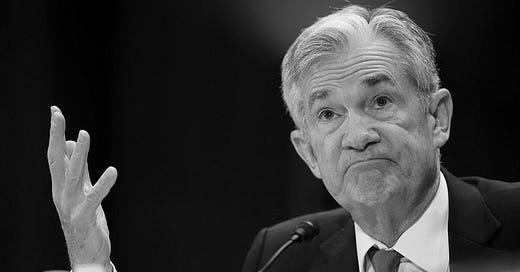

I’m only pointing out the very simple and sensible historic relationship of these rates and suggesting that since, as Chair Powell noted today, “[Central Bankers] now understand better how little we understand about inflation”, they should have now learned that their recent efforts are simply not enough.

They either want to stamp out inflation, or they don’t.